Mastering How to Calculate Investment Returns: A Practical Guide

Watching your account balance climb is a great feeling, but that number is only half the story. The real key is knowing how to calculate your investment returns using the right formula for your situation. Without this skill, you're essentially flying blind, unable to tell if your strategy is genuinely working or just getting lucky in a rising market.

You'll want to use Total Return for single investments, CAGR for comparing different options over multiple years, and XIRR if you're regularly adding or withdrawing money. Mastering these calculations turns you from a passive observer into an informed, active investor, capable of making data-driven decisions to reach your financial goals.

Why Calculating Investment Returns Matters More Than You Think

Honestly, understanding how to calculate your returns is probably the most critical skill for any investor. It's the only way to get a true report card on your financial strategy. It answers the fundamental questions: Is this investment performing as expected? Is my high-fee mutual fund actually underperforming a simple, low-cost index fund? Is my frequent trading slowly eating away at profits?

If you don't measure performance, you have no objective way to improve. This guide will demystify the core metrics that savvy investors use every day, giving you a clear roadmap to measuring what really matters.

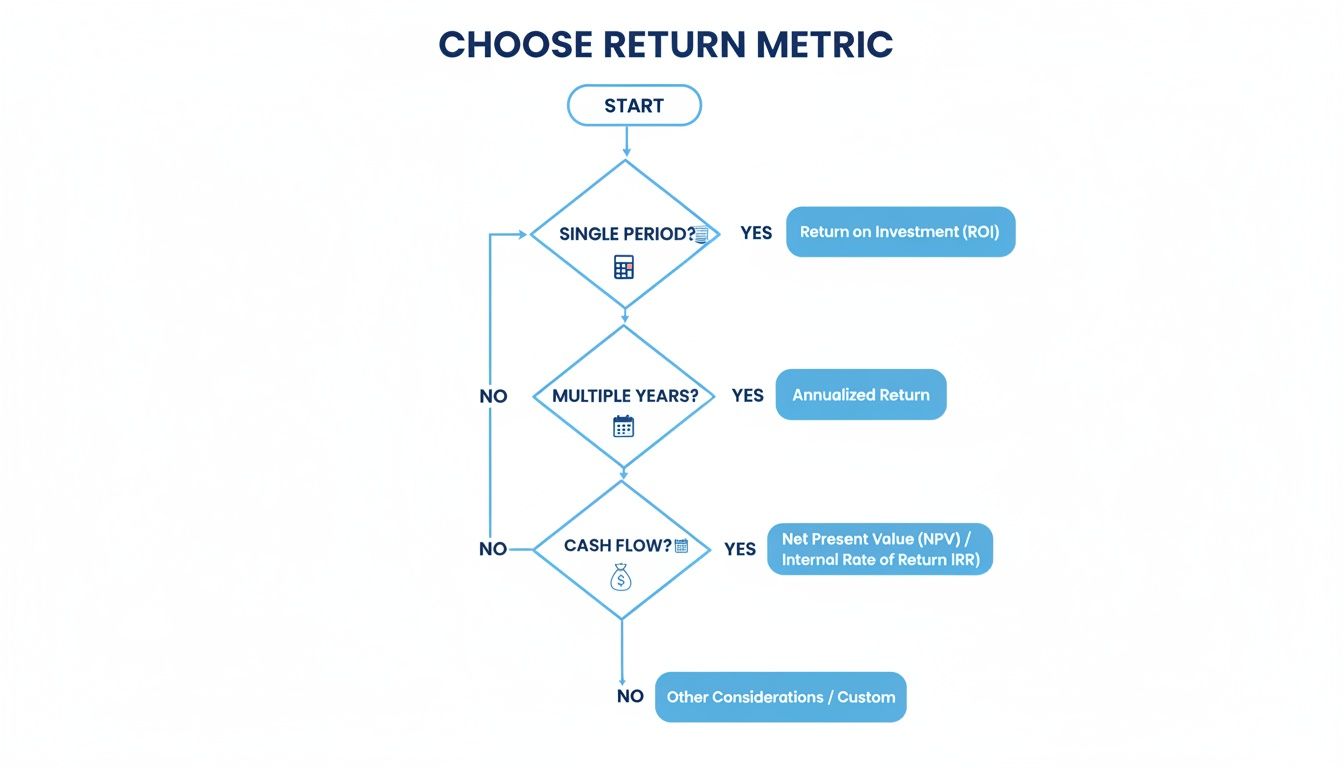

This flowchart can help you quickly figure out which metric to use based on your specific situation.

As you can see, the right calculation really depends on the investment's time frame and whether you've put more money in or taken some out along the way.

Key Return Metrics and When to Use Them

To give you a quick overview, we're going to walk through several different methods, and each one has a specific job.

This table summarizes the main calculation methods you'll learn in this guide. Think of it as a cheat sheet for choosing the right tool for the job. For more context on building a solid foundation, you might also want to explore our guide on beginner investing strategies.

| Metric Name | Best For | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|

| Total Return | Evaluating a single, static investment over a specific period. | Ignores the time it took to achieve the return. |

| CAGR | Comparing the performance of different investments over multiple years. | Assumes a steady growth rate, which isn't realistic. |

| XIRR | Calculating your true, personal return when adding or withdrawing money. | Requires more detailed data entry (dates and amounts). |

By the time you're done with this article, you'll have the confidence to go beyond just glancing at your account balance. You'll be ready to start making smarter, data-driven decisions with your money.

How to Figure Out Your Total Return on a Single Investment

If you want to know how an investment really did, the first and most fundamental metric to look at is its Total Return. This calculation gives you the bottom-line answer: how much money you made or lost, shown as a simple percentage.

It’s the perfect starting point when you’ve bought an investment and just held onto it, without adding more money or taking any out along the way.

To get this number, you just need to know what you paid for it, what it's worth now (or what you sold it for), and any cash it paid you while you owned it—like dividends. People often forget about that last part, but ignoring dividends can seriously understate how well you actually did.

The Total Return Formula Explained

The math is pretty simple. Here’s the formula you’ll use:

Total Return = ( (Ending Value – Beginning Value) + Income ) / Beginning Value

Let's quickly define those terms:

- Beginning Value: This is the total cash you put in at the start.

- Ending Value: This is what the investment is worth at the end of your measurement period. If you sold it, this is what you sold it for. If you still own it, just use its current market price.

- Income: This is crucial. It’s all the dividends, interest payments, or other cash distributions you received from the investment.

This formula neatly packages together both the change in the investment's price (capital appreciation) and the cash it spun off.

A Real-World Example: Calculating Total Return

Let's walk through a typical scenario. Say you bought 100 shares of a fictional tech company, "Innovate Corp," exactly one year ago.

- Purchase Price: You snagged them for $50 a share.

- Total Beginning Value: 100 shares × $50/share = $5,000.

During that year, Innovate Corp was kind enough to pay out a dividend of $1.50 per share.

- Total Income: 100 shares × $1.50/share = $150.

Fast forward to today, and the stock is now trading at $60 per share.

- Total Ending Value: 100 shares × $60/share = $6,000.

Now, let's plug all that into the formula:

Total Return = ( ($6,000 – $5,000) + $150 ) / $5,000

Total Return = ( $1,000 + $150 ) / $5,000

Total Return = $1,150 / $5,000 = 0.23

To turn that into a percentage, just multiply by 100. Your Total Return for the year was 23%.

See that? The $150 in dividends boosted your return by a full 3 percentage points. That's a huge difference! If you're interested in finding more investments like this, our guide on how to build passive income with dividend stocks is a great place to start.

Key Takeaway: Never, ever forget to include dividends and other income in your return calculations. If you leave them out, you’re not getting an honest look at your investment's performance.

Why Total Return is So Important

Thinking in terms of total return is essential for making accurate comparisons. History shows us just how much of a difference it makes. For example, over the last 150 years, the S&P 500's average annual return is 9.349%—but that's with dividends reinvested.

In fact, dividends have historically accounted for roughly 40% of the S&P 500's total returns. To really understand your own performance, knowing how to calculate return on investment (ROI) accurately is a foundational skill.

Where Total Return Falls Short

As useful as this calculation is, it has one major blind spot: it completely ignores time.

Think about it. A 23% return is fantastic if you made it in one year. But if it took you ten years to get that same 23% return? Not so great.

Total Return is perfect for sizing up a single investment over one continuous holding period. But it's a poor tool for comparing two different investments held for different lengths of time. For that, you need a way to put everything on an even playing field, which is exactly what we’ll cover next.

Using CAGR to Compare Different Investments Fairly

Total Return tells you what you earned, but it completely ignores how long it took. A 50% return over two years is fantastic. That same 50% return stretched out over twenty years? Not so impressive.

This is exactly where the Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) comes in. It's one of the most valuable tools you have for making fair, apples-to-apples comparisons between different investments. Think of CAGR as a way to smooth out the bumps. It gives you a single, hypothetical growth rate as if your investment grew at a perfectly steady pace each year, which is incredibly useful for cutting through the noise of market volatility.

Why a Simple Average Can Lie to You

It’s tempting to just average the annual returns to gauge performance. This is a common trap, and it can paint a wildly inaccurate picture of your actual growth.

Let's walk through a quick, classic example. Imagine you invest $10,000.

- Year 1: The market is on a tear, and your investment shoots up 50% to $15,000.

- Year 2: A brutal correction hits, and your investment tumbles by 50%, bringing it down to $7,500.

If you do a simple average of the returns (+50% and -50%), you get 0%. But did you break even? Not even close. You started with $10,000 and ended with $7,500. This is precisely the problem that CAGR solves.

The Power of the CAGR Formula

The formula for CAGR might look a bit intimidating at first glance, but it's really just three simple inputs: where you started, where you ended, and how long it took.

CAGR = ( (Ending Value / Beginning Value)^(1 / Number of Years) ) – 1

Let’s plug in the numbers from our disastrous example:

- Beginning Value: $10,000

- Ending Value: $7,500

- Number of Years: 2

CAGR = ( ($7,500 / $10,000)^(1 / 2) ) – 1

CAGR = ( (0.75)^0.5 ) – 1

CAGR = 0.866 – 1 = -0.134 or -13.4%

There it is. A CAGR of -13.4% is the true, annualized rate of loss that accurately reflects your investment's journey from $10,000 down to $7,500. It’s a far more honest number than the misleading 0% simple average.

Key Insight: CAGR is the industry standard for reporting long-term performance for a reason—it accounts for the effects of compounding. It tells you the constant annual rate your investment would have needed to grow by to get from its start to its finish.

Comparing Two Different Investments with CAGR

This is where the real magic happens. Let's say you're trying to figure out which of two investments was the better performer.

| Investment | Beginning Value | Ending Value | Holding Period | Total Return |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stock A | $5,000 | $8,000 | 3 years | 60% |

| Fund B | $10,000 | $19,000 | 7 years | 90% |

Just by looking at the Total Return, Fund B seems like the runaway winner with a massive 90% gain. But it also had more than twice as long to grow. Let's run the CAGR for each to get a fair comparison.

- Stock A CAGR: ( ($8,000 / $5,000)^(1/3) ) – 1 = 16.96%

- Fund B CAGR: ( ($19,000 / $10,000)^(1/7) ) – 1 = 9.6%

Suddenly, the picture flips completely. Stock A, despite its lower total return, was actually the superior performer on an annualized basis. It grew at a much faster clip each year. This is exactly why knowing how to calculate CAGR is so crucial for any serious investor.

Calculating CAGR in a Spreadsheet

Doing these calculations by hand gets old fast. Thankfully, both Google Sheets and Excel make this a breeze.

You can use either the POWER function, which is a direct translation of the formula, or the built-in RATE function.

Using the POWER Function:=POWER(Ending Value / Beginning Value, 1 / Years) - 1

Using the RATE Function:=RATE(Years, 0, -Beginning Value, Ending Value)

A quick note on the RATE function's inputs:

- Years: The number of years you held the investment.

- 0: This field is for periodic payments, which we're assuming are zero.

- -Beginning Value: Your initial investment must be entered as a negative number because it's a cash outflow.

- Ending Value: The final value of the investment.

Both functions will give you the exact same CAGR, letting you analyze your portfolio like a pro. If you're curious about how these calculations apply to common investments like mutual funds, our guide on how to start investing in index funds is a great next step.

Don't underestimate the long-term impact of compounding. For perspective, a $100 investment in the S&P 500 back in 1928 would have grown to over $1,800,000 today with dividends reinvested. This incredible growth is best understood by its long-term CAGR of roughly 10.3%—a far more useful metric than a simple average because it accounts for decades of volatility.

While CAGR is fantastic for comparing historical performance, more complex scenarios with multiple cash flows might require different tools. For instance, an internal rate of return calculator for real estate can provide an even more powerful metric for those specific kinds of investments.

What Happens When You Add or Withdraw Money?

Real-world investing is messy. Very few of us just drop a lump sum into an account and then walk away for 30 years. Life doesn’t work like that.

We contribute to our 401(k) with every paycheck. We add a little extra to our brokerage account when we get a bonus. And sometimes, we have to pull money out for a down payment or an emergency.

These comings and goings—the cash flows—completely throw off simple calculations like Total Return or CAGR. Those formulas just aren't built to handle the timing of multiple deposits and withdrawals. This is where you need a much smarter tool.

The answer is a metric called the Internal Rate of Return (IRR). I know, it sounds a bit intimidating, but the concept is straightforward. It calculates your true, personalized annual return by taking into account the exact timing and size of every single dollar you put in or take out.

Meet XIRR: The Investor's Best Friend

In the real world, you'll almost always use the spreadsheet version of this formula. It's called the XIRR function in both Google Sheets and Microsoft Excel. Honestly, this little function is the gold standard for tracking your own portfolio's performance.

Why? Because it finally answers the most important question: "Given when and how much I invested and withdrew, what was my actual compound annual growth rate?"

XIRR shows you how your own decisions—your timing—impacted your results. Did buying that dip in March actually help? Did pulling out cash for a new car hurt your performance? XIRR tells that story, which is far more useful than just looking at a fund's generic performance chart.

A Real-World Example: Setting Up XIRR

Let's walk through a classic scenario where XIRR is indispensable. Imagine you’re contributing to an IRA. You start the year with a balance, add money every month, and want to know your real return at the end of the year.

All you need is a simple spreadsheet with two columns: one for the dates and one for the cash flows.

There's just one crucial rule you have to remember for the cash flow column:

- Money IN (like your contributions or initial investment) must be a negative number.

- Money OUT (like withdrawals or the final account value) must be a positive number.

Let's build it out. Say you start on January 1st with $10,000. You then invest an additional $500 on the first of every month from February through December. On New Year's Eve, you check your account and see a final value of $16,500.

Your spreadsheet would look like this:

| Date | Cash Flow |

|---|---|

| 1/1/2024 | -10,000 |

| 2/1/2024 | -500 |

| 3/1/2024 | -500 |

| 4/1/2024 | -500 |

| 5/1/2024 | -500 |

| 6/1/2024 | -500 |

| 7/1/2024 | -500 |

| 8/1/2024 | -500 |

| 9/1/2024 | -500 |

| 10/1/2024 | -500 |

| 11/1/2024 | -500 |

| 12/1/2024 | -500 |

| 12/31/2024 | 16,500 |

See how the initial $10,000 and all the $500 contributions are negative? And the final value is positive? That’s the key. This tells the formula "this is what I put in, and this is what I ended up with." Making consistent contributions like this is a cornerstone of good financial health, and if you're looking to tighten up your finances, our guide on how to create a monthly budget is a great place to start.

Now for the magic. In any empty cell, just type =XIRR(cash_flow_range, date_range).

The answer you'll get is 9.79%. That's it. That is your true, personalized, annualized return for the year, perfectly accounting for the fact that your money went in at different times.

The Hidden Costs That Reduce Your Real Return

The number you see on your statement isn't what you actually get to keep. Knowing how to calculate investment returns is a great start, but the real skill is understanding the difference between your gross return and the net return that actually lands in your pocket.

There are three silent partners in every investment you make: fees, taxes, and inflation. They're constantly working to reduce your profits, and ignoring them is one of the biggest mistakes an investor can make. Your goal isn't just to make money; it's to grow your purchasing power.

The Slow Drag of Investment Fees

Investment fees might seem harmless—often just a percent or two—but they are deceptively destructive over the long haul. Because they chip away at your balance year after year, they create a "compounding drag" that can seriously stunt your wealth.

Let’s run a quick scenario. Imagine you invest $100,000 and earn an average of 7% annually over 30 years.

| Fee Structure | Expense Ratio | Final Portfolio Value (30 Yrs) | Fees Paid |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Fee Fund | 0.1% | $717,000 | ~$13,000 |

| High-Fee Fund | 1.1% | $557,000 | ~$133,000 |

| Difference | 1.0% | ($160,000) | $120,000 |

That seemingly insignificant 1% difference in fees just cost you $160,000. It's a staggering amount of your own money, gone forever.

My Two Cents: Always, always check the "expense ratio" on any mutual fund or ETF you're considering. Sticking with low-cost funds is one of the simplest and most effective ways to keep more of your own money.

Navigating Capital Gains Taxes

When you sell an investment for a profit, Uncle Sam wants his share. This is called a capital gains tax, and the rate you pay depends entirely on how long you held the asset.

- Short-Term Capital Gains: If you buy and sell an investment within one year or less, your profit is taxed at your ordinary income tax rate. This is the same, higher rate you pay on your salary.

- Long-Term Capital Gains: If you hold an asset for more than one year, your profit gets a much better deal. It's taxed at a lower, preferential rate—for most people, that's 0%, 15%, or 20%.

The lesson here is simple: patience pays off. Making frequent trades can subject your gains to much higher tax rates, seriously shrinking your net profit. A great way around this is using tax-advantaged accounts like a 401(k) or IRA, which let your money grow without the annual tax drag. If you're looking to put your money to work, you can explore the best ways to invest cash to maximize your returns in our detailed guide.

Your Real Return After Inflation

Inflation might be the most overlooked cost of all. It’s the silent thief that erodes the value of your money every single day. A 10% nominal return feels fantastic, but if inflation was 3% that year, your actual purchasing power only grew by about 6.8%. That’s your real return.

A deep dive into global stock markets found that while the U.S. delivered a real (inflation-adjusted) annual return of 4.73% between 1900 and 1996, the median for other countries was just 1.5%. This is a perfect example of why focusing on real returns is the only way to know if you're truly getting ahead.

Let’s see how this plays out with a practical example. Imagine you start with a $10,000 portfolio.

Nominal vs. Real Return: A Practical Example

| Year | Nominal Return | Inflation Rate | Real Return | Portfolio Value (Real Terms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start | – | – | – | $10,000 |

| Year 1 | 8% | 3% | 4.85% | $10,485 |

| Year 2 | -5% | 4% | -8.65% | $9,578 |

| Year 3 | 12% | 2% | 9.80% | $10,517 |

Notice how even with a strong 12% nominal return in Year 3, the real value of the portfolio barely recovered from the previous year's loss once you account for inflation. This is why calculating your real return isn't just an academic exercise—it’s the only way to know if you're actually building wealth.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. What's the difference between Time-Weighted and Money-Weighted Return?

A Time-Weighted Return (TWR) measures the performance of the investment itself, ignoring your contributions or withdrawals. It's what mutual funds report. A Money-Weighted Return (MWR), which is what XIRR calculates, measures your personal performance, including the timing of your investment decisions. Use TWR to compare funds and MWR to evaluate your own results.

2. How do I calculate returns on an investment I haven't sold yet?

You use the current market value as the "Ending Value" in your calculation. The profit is called an "unrealized gain." This allows you to track performance without needing to sell the asset.

3. What's the best online calculator for investment returns?

For simple, one-time calculations, many online tools work well. However, for tracking a real portfolio with ongoing contributions, the best tool is a spreadsheet program like Google Sheets or Microsoft Excel. Learning the XIRR function provides the most accurate and personalized results.

4. Why is my broker's return different from my calculation?

This is usually because your broker reports a Time-Weighted Return (TWR), while your personal calculation using XIRR is a Money-Weighted Return (MWR). Since you have likely added or withdrawn money, the two figures will differ. Your MWR is a more accurate reflection of your personal experience.

5. What is a "good" investment return?

A "good" return is relative and depends on your risk tolerance and financial goals. A common benchmark is the long-term average annual return of a broad market index like the S&P 500, which has been around 9-10%. A good return for you is one that keeps you on track to meet your goals without taking on excessive risk.

6. How do stock splits affect my return calculation?

Stock splits do not affect your total return calculation. A split increases the number of shares you own but decreases the price per share proportionally, leaving the total value of your investment unchanged. Your "Beginning Value" remains the same.

7. Should I calculate returns before or after taxes?

You should be aware of both. Pre-tax returns are useful for comparing the performance of different investments on a level playing field. However, your after-tax return is what truly matters, as that's the profit you get to keep. Always consider the tax implications of your investment strategy.

8. Does a negative return mean I made a bad investment?

Not necessarily. All investments carry risk, and short-term negative returns are a normal part of market volatility. A "bad" investment is one that consistently underperforms its benchmark over the long term or no longer aligns with your financial goals.

9. How often should I calculate my investment returns?

For most long-term investors, calculating returns quarterly or annually is sufficient. Checking too frequently can lead to emotional decision-making based on short-term market noise. The goal is to ensure your long-term strategy is on track, not to react to daily fluctuations.

10. Can I use these formulas for rental property investments?

Yes, absolutely. The XIRR formula is particularly well-suited for real estate. Your initial purchase price and any capital improvements are negative cash flows (money out), while your net rental income and the final sale price are positive cash flows (money in). This will give you the true internal rate of return for the property.

At Everyday Next, we believe that understanding your money is the first step toward building a better future. Our guides are designed to give you the clarity and confidence you need to make smart financial decisions. To continue your journey, explore more insights on wealth, tech, and personal growth at https://everydaynext.com.